Because Science Say So

- Lydia Dadson

- Oct 30, 2023

- 6 min read

Why do I train dogs the PoochWise Way? Well, in short because research and studies have been conducted over many years to build a picture of how dogs learn, which means I can target the training methods used for best results for your dog to flourish.

It's a [insert dog breed] thing

Yes each dog has their own personality. But the fundamental's of how they learn are very similar. Breed only dictates around 10% (Morrill et al, 2022) of behaviour which means 90% of dogs’ behaviours are incredibly similar. So, whether you are training a Beagle or a Shih Tzu with inappropriate behaviour issues such as, barking, lounging or messing in the house, engaging the Beagle’s nose will be a likely route to de-stress the dog. Beagles were sniffer dogs used to hunt and sniff out foxes. Similarly, even though Shih Tzu are lap dogs from royal palaces, engaging that dog’s nose will also benefit them. Regardless of what the dogs’ were bred for, their shape or size, they are fundamentally dogs.

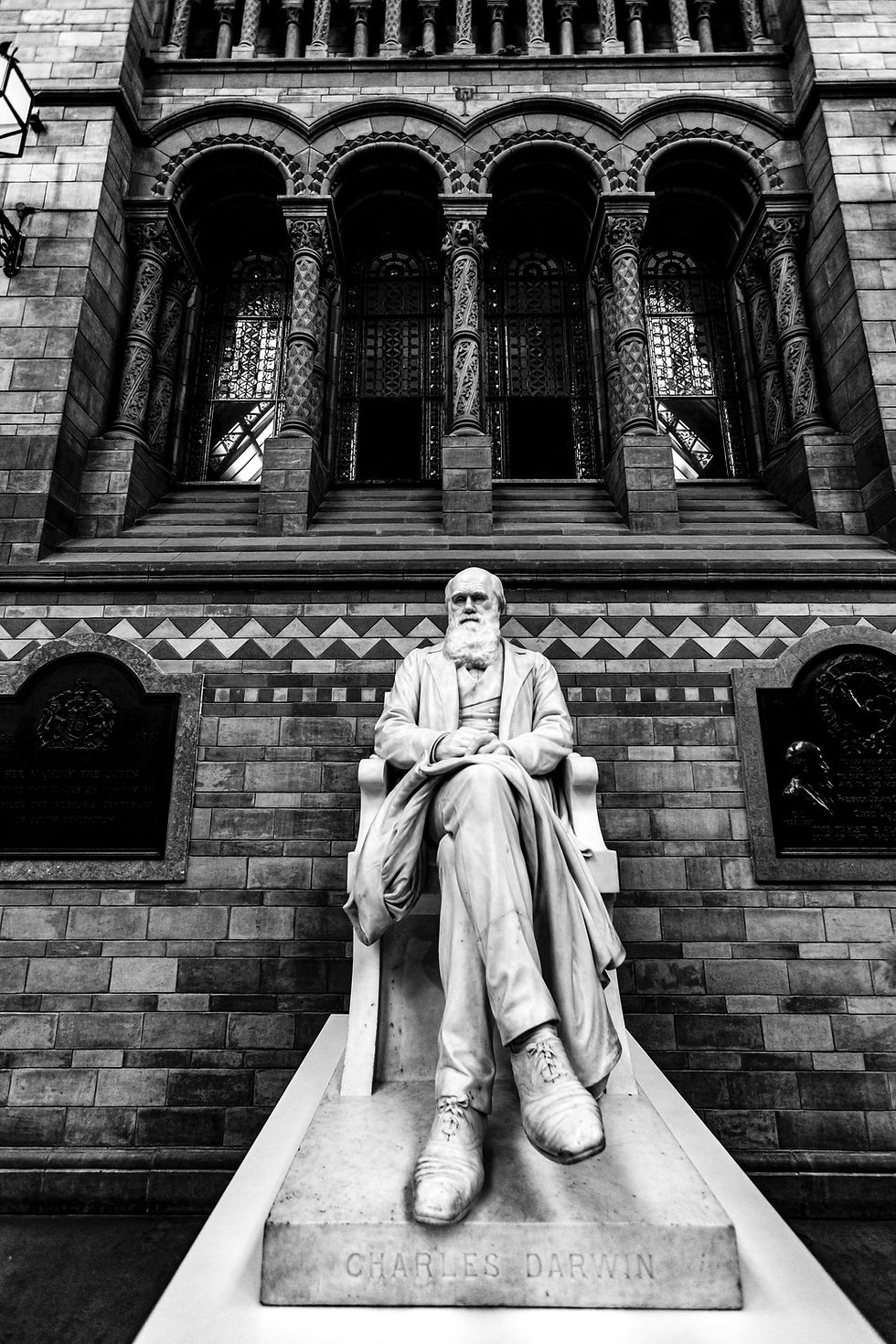

Founding fathers on Dog behaviour

Ethology (the science of animal behaviour) can be found in Douglas Spalding (1873) work who observed ‘imprinting’ in chicks. Ethology is also found in the work of Charles Darwin who categorised behaviour into ‘instinctive’ which was observed in natural selection and ‘learned behaviours’ (Bolman, 2022). Darwin (1909) claimed animals inherited behaviour and physical characteristics which could change, depending on genetic and environmental factors. Later questioned by Richard Burkhardt (2005) who argues during the early stages of social behavioural studies of dogs, the categorisation of ‘instinct’ is too simplified and there was more to reveal about dogs.

Why do we care?

Ethology asks the question how and why animals do the things they do, which allows ethologists to increase animal welfare. This is because having an in-depth understanding of a dog’s life gives people the opportunity to make changes that will benefit the dog’s overall health and wellbeing. Ethology is the biological study of animal behaviour with the goal to help understand animals to improve their care and lives.

Dawkins (2008) explains that once the science was known attitudes and decisions towards animals may change how we perceive them, for example that they can feel pain. A better awareness of dog welfare generally has led to the concerns for certain tools such as E collars (Masson et al, 2018). Moreover, campaigners for the ban of electric shock collars who believe them to be cruel has led to a recent update in legislation to ban them in the UK from February 2024 (The Kennel Club, 2023). Finding out the facts means that people can communicate and care for dogs in a more efficient and mutually beneficial ways.

How Dogs Learn

Classical conditioning

In 1930s, the Nobel Prize winners Lorenz and Tinbergen promoted Ethology as a biological study of behaviour. Whether Ethology was the biological or psychological study of behaviour, an important piece of science to note in behavioural investigation, was Pavlovian (or classical) conditioning. Ivan Pavlov (1932) conducted a study with dogs observing that they salivated at their food. Pavlov added a bell to ring at the same time as the dogs ate. Later in the study Pavlov, just rang the bell and the dogs salivated even though no food was presented. This is now known as classical conditioning.

Classical conditioning is a way dogs learn. Pavlov found that in theory anything could become a stimulus to the dog when paired with an action. Dogs are likely to learn from forward conditioning which means the stimuli happens first before the conditioned response (Chang, et al, 2004). Moreover, classical conditional learning could happen after one encounter, for instance if the animal had a strong emotional or biological response, known as one trial learning. Classical conditioning can be reversed if required (Jones, 1924), by introducing the fear stimulus in this scenario, a bike and pairing it with something positive (more on desensitisation and counter conditioning in upcoming Blog post).

Operant Conditioning

Edward Thorndyke (1911) termed operant conditioning where he concluded animals learnt via trial and error in his study, and the animals would remember and perform quicker next time. Consequently, learning happens faster when the reinforcer is given straight after a behaviour. The gap between the behaviour and reward being short means dogs will learn the consequence of the behaviour quicker. This is also known as the law of effect which means that behaviour has consequence.

Stages of Learning

Critical Period

Part of Behaviourist Theory was the new understanding of critical period (Scott and Marston, 1950). In the 1950s the 'critical period' was set out as a key phases of development in a dogs' life and 'learning' (Bolman, 2022). Scientists who used this framework in their studies found that there were certain periods when dogs started to crawl or fight with their siblings. Three main stages in a dog's development were identified (Feuerbacher and Wynne, 2011, p.56)

Neonatal

Socialisation

Sexual maturity

In a world where you can be anything, be kind

Old school training methods have been found to harm the human dog relationship rather than foster it (Greenebaum, 2010). Causing stress and inhibiting dogs from performing dog behaviours in adverse and harsh ways will only diminish the dog’s welfare and the relationship they have with their owner (Fernandes et al., 2017). The idea that dogs need to be dominated and confronted is a way to increase aggression in dogs (Herron et al., 2009).

In the last 20 years popularised training methods have moved onto building trusting relationships between dogs and humans using rewards (Hens, 2009). ‘Reward dog training teaches behaviour modification and refocusing techniques through food rewards’ (Greenebaum, 2010, p. 140). Moreover, people have been encouraged to be kind to dogs as early as Medieval times (Menache, 2000).

Using Ethological study to understand dogs’ behaviour gives us a great insight into what and how a dog may respond to training. For instance, ethological study has highlighted many areas that may have been overlooked in the past when communicating with our dogs, to get a desired result. One such example was a dog’s use of their nose as ‘odours and olfaction play a major role in behavioural development and expression in animals’ (Nielsen, et al, 2015). Odours form a major component of the animals’ surroundings, they cannot and should not be ignored whenever our aim is to improve animal welfare (Nielsen, et al, 2015). Therefore, by using a dog’s natural ability to sniff for food or to get a reward, the odours themselves may become ‘environmental enrichment’ (Nielsen, et al, 2015, p.2).

Citations

Bolman, B., 2022. Critical Periods in Science and the Science of Critical Periods: Canine Behavior in America. Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, 45(1-2), pp.112-134.

Burkhardt, R.W., 2005. Patterns of behavior: Konrad Lorenz, Niko Tinbergen, and the founding of ethology. University of Chicago Press.

Chang, R., Stout, S. and Miller, R., 2004. Comparing excitatory backward and forward conditioning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Series B Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 57(1), pp.1-24.

Darwin, C. and Darwin, C.R., 1909. The origin of species (pp. 95-96). New York: PF Collier & son.

Dawkins, M.S., 2008. The science of animal suffering. Ethology, 114(10), pp.937-945.

Fernandes, J.G., Olsson, I.A.S. and de Castro, A.C.V., 2017. Do aversive-based training methods actually compromise dog welfare?: A literature review. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 196, pp.1-12.

Feuerbacher, E.N. and Wynne, C.D., 2011. A history of dogs as subjects in North American experimental psychological research. Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews.

Greenebaum, J.B., 2010. Training dogs and training humans: Symbolic interaction and dog training. Anthrozoös, 23(2), pp.129-141

Hens, K., 2009. Ethical responsibilities towards dogs: An inquiry into the dog–human relationship. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 22, pp.3-14

Herron, M.E., Shofer, F.S. and Reisner, I.R., 2009. Survey of the use and outcome of confrontational and non-confrontational training methods in client-owned dogs showing undesired behaviors. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 117(1-2), pp.47-54

Jones, M.C., 1924. The elimination of children's fears. Journal of experimental psychology, 7(5), p.382.

Masson, S., de la Vega, S., Gazzano, A., Mariti, C., Pereira, G.D.G., Halsberghe, C., Leyvraz, A.M., McPeake, K. and Schoening, B., 2018. Electronic training devices: discussion on the pros and cons of their use in dogs as a basis for the position statement of the European Society of Veterinary Clinical Ethology. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 25, pp.71-75.

Menache, S., 2000. Hunting and attachment to dogs in the Pre-Modern Period. Companion animals and us: Exploring the relationships between people and pets, pp.42-60.Reid, P.J., 2009. Adapting to the human world: dogs’ responsiveness to our social cues. Behavioural processes, 80(3), pp.325-333.

Morrill, K., Hekman, J., Li, X., McClure, J., Logan, B., Goodman, L., Gao, M., Dong, Y., Alonso, M., Carmichael, E. and Snyder-Mackler, N., 2022. Ancestry-inclusive dog genomics challenges popular breed stereotypes. Science, 376(6592), p.eabk0639.

Nielsen, B.L., Jezierski, T., Bolhuis, J.E., Amo, L., Rosell, F., Oostindjer, M., Christensen, J.W., McKeegan, D., Wells, D.L. and Hepper, P., 2015. Olfaction: an overlooked sensory modality in applied ethology and animal welfare. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 2, p.69

Pavlov, I.P., 1932. The reply of a physiologist to psychologists.

Scott, J. and Marston, M.V., 1950. Critical periods affecting the development of normal and mal-adjustive social behavior of puppies. The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology, 77(1), pp.25-60.

Spalding, D.A., 1873. Instinct. With original observations on young animals. Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, 17, p.424.

Thorndike, E.L., 1911. Animal intelligence: Experimental studies. Transaction Publishers.

The Kennel Club, 2023. 'Cruel' electric shock collars banned in England. The Kennel Club. Viewed: 15/05/2023. Available at: https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/media-centre/2023/april/cruel-electric-shock-collars-banned-in-england/#:~:text=In%20a%20'historic%20moment%20for,ten%20year%20campaign%20to%20%23BanShockCollars.

Comments